A Very Short Overview of the Dress and Adornment of the Southeast IndiansA condensed version of a talk from Fur, Feathers, and Fabric by Paula and Don Sanders*

Map 1 shows the areas considered to be the homeland of the Southeast Indians. The colored areas are called cultural areas because the inhabitants share more similare traits than those who live outside these cultural area. these areas are not static areas, but are fluid and evolving. Map 2 shows the location of some of the Indian subdivisions that will be discussed throughout this talk. When people living in the twentieth century think of the dress of the Southeastern Indians, they very often associate it with a particular tribe and assign aspects of dress accordingly. This concept, however, has proven to be very fallacious.

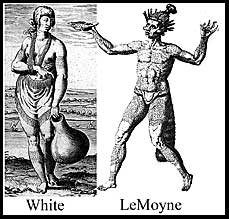

One of the first people to depict the Indians was Jacques Le Moyne went with an expedition to Florida in 1564 but did his artwork upon his return to England. One must look at the artwork in the context of the European culture at the time. John White went to the Roanoke area of North Carolina in 1585. He, however, did his arwork in situ, but it was reproduced later by William DeBry and one can only guess at the changes made. Most of the groups were not stratified although there were exceptions.

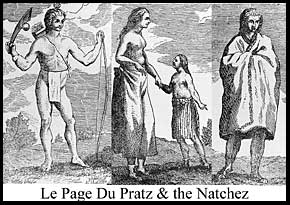

The clothing varied little between the leaders and The picture of the European Cavalier gives an indication of some of the garments given to the Indians. The Indian woman on the right is wearing a jerkin. In a report by Durant de Dauphine she wore it when she went to visit William Fitzhugh's at his plantation on the Potomac River in 1686. She probably wore it out of respect for this White family. In 1718, Le Page du Pratz arrived in the colony of Louisiana and wrote a book in French entitled Histoire de la Louisiane on various aspects of Louisiana including the customs, mores, etc. of the Natchez Indians in whose vicinity he lived for about eight years. His book was published in France in 1758 and, then, translated into English at various points during the next twenty years. Unfortunately, much of the observations of the dress and customs of the Natchez Indians were translated incorrectly. This led to many inconsistent and incorrect statements on Natchez dress in books written in the twentieth century. The illustrations bellow are taken from his book.

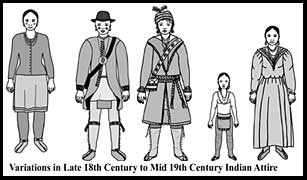

As the Europeans and, then, the Euro-Americans increased their associations and power over the Indians through a control of market goods, land acquisitions, decimation by war, diseases, and slavery of the Native populations, the Native society became socially and economically stratified with the leaders being usually those of mixed blood. As a result, wealth became an important factor and represented power and prestige. The Indians began to accumulate goods beyond those necessary for survival. These included jewelry and fancy clothing much of which was adopted from the dress of the White Man. Starting in the mid-eighteenth century, clothes among male became a differentiating status symbol.The adoptation of "White dress", spurred on by the Christian missionaries, became a symbol of civilization and conversion to Christianity. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the dress of both sexes was still basically non-tribally representative. It had more to do with an individual's mixture of blood (White and Native), proximity to Euro/Americans, position within the Native community, socio-economic status, and Christianization. Native Americans were not the only ones whose dress was influenced by another. The White man's dress was influenced by his Native American counter part. During the eighteenth century, especially toward the end, many "White" Americans left the Atlantic seaboard and headed in a westerly direction toward the colonial frontier.

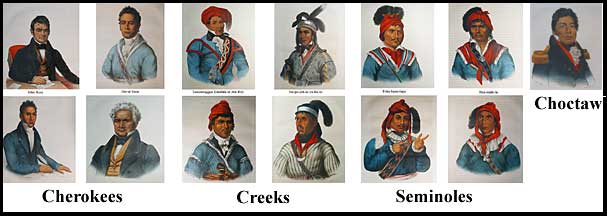

The hunting smocks were designed as tunics and belted at the waist. Sometimes they had fringed yokes or capes attached. They, also, were open in front, sometimes belted in back, and decorated with fringes, pleats, and arm bands near the elbow. The sleeves were often full ending in a tight cuff. However, their designs varied according to the fancy of the wearer. As "White" American families followed the first male pioneers, much of the leather clothing was replaced by homespun materials. The hunting shirt began to be made of linsey-woolsey. It was often dyed blue and decorated with yellow fringe, but it still retained its individualistic design. There are different opinions as to the origin of the hunting shirt or smock. Some historians believe it to be of Indian origin. If this is true, there is no indication that it originated with the Southeastern Indians. Others believe that it grew out of the "simple frock of the farmer or labourer of the day." "White" American women on the frontier dressed in simple homespun. These women wore their hair in plates or gathered in a knot at the back. Hats were rarely worn; hoods or shawls were used in inclement weather. The women wore on their feet either stout square-toed shoes, moccasins after the Indian fashion, or nothing in warm weather. The pioneer men and women lived, obviously, more closely to the Indian than did the gentry. However, as can be seen from paintings and as described in journals, the Indians adopted clothes from both classes of society and, often, held them in value according to their societal class of origin. The paintings below are from the McKenney-Hall Collection.

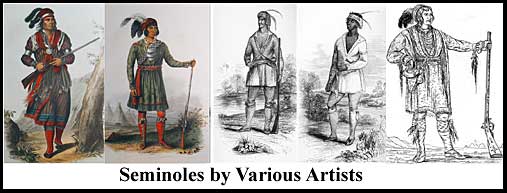

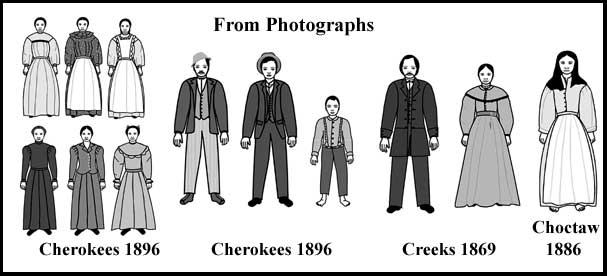

As the nineteenth century opened, many Indian leaders considered education for their youth to be very important. Missionary day and boarding schools were established with strict dress codes that emphasized "White" American dress. As the nineteenth century continued, while some Native men still wore, what is historically considered to be "traditional" dress- breech clout, leggings, and moccasins, very few women went bare chested. Most women wore some adaptation of the American frontier dress. Some, especially mixed bloods from influential and wealthy families, dressed as did any White woman of a similar stratifation level. From the end of the eithteenth century until the middle of the nineteenth century, Indian males adapted components of "White" fashion on a very individualistic basis that was not tribally sensitive. The Indian women's clothing evolved in a different manner than that of the men. It was never as intricate or inventive nor was it based soley on "White" women's fashion. While many wore "White" women's pioneer styled dresses, others wore clothing that was handy such as men's shirts and waistcoats. Their clothing, also, was not tribally sensitive. The only tribe that had identifying clothing was the Seminole and that did not evolve fully until the very late nineteenth century.

By the late nineteenth century while some Native American males still wore hunting shirts, many Native Americans, both men and women, especially the mixed bloods, wore what could be termed "White Man's" clothing. It is important to note the similarities of dress inter-tribally and the dissimilarities intra-tribally or within the tribe.

The dress of these Native Americans from the Southeast shows how a group of people first adapted to their environment and then adapted and evolved as their circumstances changed. Throughout the whole study of the Dress and Adornment of these Native Americans, have demonstrated their ingenuity and individualism in adapting and adopting different forms of attire. *Please note: Since the quotations are taken from a talk given by the Sanders, the actual references are not given here. However, all are authenticated and reproduced in their book, Fur, Feathers, and Fabric. |

||||

The

dress of the Indians when first observed by the late fifteenth

and early sixteenth century explorers, was, primarily, climate

oriented. The natives used materials found in their environment

and adapted them to their need. Their clothing was minimal and

their adornment consisted of permanent tattooing, painting, and

the wearing of jewelry in and from selected appendages.

The

dress of the Indians when first observed by the late fifteenth

and early sixteenth century explorers, was, primarily, climate

oriented. The natives used materials found in their environment

and adapted them to their need. Their clothing was minimal and

their adornment consisted of permanent tattooing, painting, and

the wearing of jewelry in and from selected appendages.

followers.

As early as 1649, an Englishman, William Bullock, advocated dressing

the most tractable Indian "kings" in such a manner as

to create a system of competition and a market for European goods.

He, also, advocated paying them in "Cloake, or Breeches,

and Doublet, or the like."

followers.

As early as 1649, an Englishman, William Bullock, advocated dressing

the most tractable Indian "kings" in such a manner as

to create a system of competition and a market for European goods.

He, also, advocated paying them in "Cloake, or Breeches,

and Doublet, or the like."

Initially

these pioneers made their clothes from tanned hides after the

Indian fashion. The men usually wore leather hunting smocks, leggings,

and moccasins. For an undergarment, they, often, wore the breech-clout.

Initially

these pioneers made their clothes from tanned hides after the

Indian fashion. The men usually wore leather hunting smocks, leggings,

and moccasins. For an undergarment, they, often, wore the breech-clout.